PALACIO DE MARCHENILA

Located in the neighborhood of San Bartolomé, the

house that occupies number 18 of

the Conde de Ibarra street in Seville, is a clear example of Sevillian noble

architecture, which evolved from the late medieval to the baroque, from

nineteenth-century tastes to adaptation for administrative use with current

criteria. The street where the house is located, today Conde de Ibarra, was

named in the XV century of Toqueros, because it was installed in it by textile

craftsmen who made toques.

Supported its facade on the old Jewish wall, the

structure of the house recalls the typical Roman and Muslim houses, where the

courtyards and gardens take center stage and symbolically lead us to Roman

Olympus, Christian Eden and Muslim paradise. These open spaces have lasted over

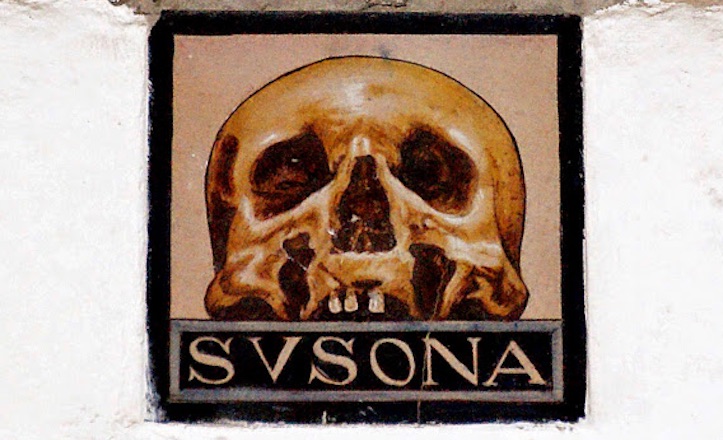

time adapting to new needs. The first documented references to his occupation

lead us to the seizure of the assets of the Jewish religious minority expelled

from the neighborhood of San Bartolomé and of his donation, by Enrique III, to

the justice of the land Diego López de Zúñiga, who was also the owner of the

neighbor Palace of Altamira.

In the second half of the 15th century it was again donated to the bachelor

Fernando Díaz de Córdova, whose children would sell it in 1483 to Pedro Manuel

de Lando, illegitimate son of a Sevillian family of nobility, councilor of the

town council since 1474, who was benefited by the Catholic Kings for their

frequent and loyal support for the crown. In 1502 it passed into the hands of

the Alcocer family, contractors transporting goods and slaves to the Indies.

Descendants of the latter occupied the house during the sixteenth and seventh

centuries and will be in the last decades of the eighteenth century when it

falls on the family of hidalgos of Santa Marina.

In the last third of the eighteenth century we saw the

semi-ruinous state in which the house was located, so the municipal council

urges its rehabilitation or forced sale to anyone who can carry out its

reconstruction. The situation causes its sale by auction, being acquired by Don

Francisco Keyser, a Ghent flamenco merchant based in Seville.

From this moment, the house takes on special splendor, endowing itself with

the physiognomy that we recognize today, even modifying part of its exterior by

settling one of its façade angles to remedy its narrowness, facilitating the

passage of carriages. Likewise, the Flemish merchant tried to make his back -

with access to the street that is still called Levíes and in which there was an

alley that was always cause for complaint to favor the shelter of homeless and

thugs - was part of the housing, at the same time that it allowed the private

access of carriages, for which it urged in several occasions to the Cabildo in

order to propose the new use always receiving the refusal of this one. This

period of modifications ends with the century when the Keyser family lost the

property due to a judicial embargo attributed to the efforts made by a partner

of the merchant with whom he had contracted a large debt.

Throughout the nineteenth century sales and temporary

transfers with their consequent changes of residents, until in 1854 the house

is purchased by the Romero family, military high-ranking participants in the

wars of independence and emancipation of the Spanish colonies .

The widow of the distinguished military man will

bequeath to his grandchildren, being, among them, Cecilia who would maintain

the property until the beginning of the 20th century, transferring it to her

children, who will live there until 1934.

From 1937 the house was used as a free Catholic

school, a residence for noble families and, from 1940 onwards, a printing

workshop for a businessman from A Coruña. Subsequently it would be the property

and commercial headquarters of Miguel Ybarra Pharmaceutical Industries, who was

mayor of the city between 1940 and 1943. Small bourgeois representative of an

emerging self-sufficient industry that would install in the house its

laboratory and warehouse until, at the end of the years Sixty, the company will

disappear.

Once again, the inheritance and the distribution led

this farm to change owners, remaining in 1969 in the hands of the Discalced

Carmelites of San José de Dos Hermanas, being mortgaged by them as an economic

resource in 1977.

The farm, as it will happen in many of the surrounding

manor houses, suffers from that moment the consequences of abandonment and

degradation, being practically in a ruinous state. During this period is

acquired by a real estate group that aims to unify several properties to

convert them into garages and homes -in which we are concerned was built part

of a basement in the rear area- without the management came to occur. P.G.O.U.

of Seville in 1985 declared it as a palace, suggesting expropriation to avoid deterioration.

Of the building we can emphasize in the first place

its facade, divided in three bodies and where the restoration has been more

intense integrating the remains found, of classic drawings and avitoladas

lines. The apilastrado of the same and part of his rejería shows us its richest

aspect. The ground floor, the main door, centered, of great size crowned with

blazon, that gives access to the vestibule. The second body is structured with

large windows and balcony with tejaroz. The last floor has a series of windows

with a gable roof, possibly destined for storage.